In the first edition of this series, I wrote about harsh light, and the challenges and opportunities those conditions create for photographers. In this post, I want to talk about another form of challenging light (a term I prefer to “bad”): flat light.

Flat light is unquestionably tricky to work with. While uniform overcast light can be effective for wildlife and human portraiture, when it comes to landscape… well, I’m not sure “challenging” is strong enough of a term.

Wildlife

First, wildlife: In Africa for the past couple of trips, I have timed my Discover Botswana workshops to coincide with the arrival of the green season. There are a few advantages to this time of year, but the biggest is the strong chance for afternoon clouds. The overcast light greatly increases the hours of quality shooting light for wildlife. And it should come as no surprise that flat overcast can be effective for wildlife. Softbox light is used all the time in portraiture, and when the entire sky becomes cloud-covered softbox? Well, details emerge in feathers and fur, colors become uniform, hot highlights fade away. It’s simply effective.

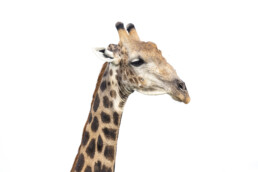

But, exposures really matter here. The two images below were shot against a bright white overcast sky. (I’ll dive more into this backlight shooting situation in the next post). To make the details in the Tawny Eagle and giraffe really pop, you simply let the backdrop go to full, blown-out white. The result is essentially a cutout, but it’s effective nonetheless.

Landscapes

Landscapes thrive in contrast and shadows, something flat light does not provide. The result is images that look dull, lacking contrast and color. And even my tried and true black and white conversions rarely can salvage such a photo.

There are exceptions of course. Fog creates light as flat as can be, but can yield beautiful photos. Scudding clouds, rain, and textured clouds can save an image made dull by flat light. If the overcast is textured, or better yet, dramatic, even if the landscape itself is muted, the sky can make up for it. Here are a couple of photos from Gates of the Arctic National Park taken on a day of dense overcast. The savior, however, was the texture and drama in the clouds, and the colors (autumn foliage, and blue water) that were enhanced by the flat light.

That raises a point. Foreground colors tend to pop in flat overcast conditions. Even if the major landscape features look lousy, the details of flowers, autumn colors, lichens, river stones, and all the other elements of the landscape can look exceedingly good.

Photography success on such days is a matter of shifting our expectations, rather than giving up. Being flexible, and willing to work with different conditions, that’s a key to making images that work.

Here is a small gallery of images shot under overcast, flat light. As you can see, intimate landscapes, as Eliot Porter called the details of the scene, play a big part in these photos.

The next and final post in this series will look at back light. We’ll build a bit on the idea of over-exposure to create the cutout look I described above, but also how direct, strong sunlight, from tricky angles, can be used to create something interesting.