Today, I was doom-scrolling Facebook, and I came across a post from wildlife photographer Dawn Wilson. I like Dawn’s work. She’s creative and isn’t scared to post images that are outside the norm for most wildlife and outdoor photographers. The post that grabbed my attention was an image of a couple of pelicans sitting atop pylons over the water. The light is HARSH. She described the conditions as low fog burning off with bright sun overhead. In short, high contrast. Her interpretation of the shot is really nice. High key (blown to white) background, nearly black subject of the birds, and lightly saturated, blue water. It comes together nicely. Check out the image

HERE.

The bone I pick is her caption (sorry, Dawn) as she describes it as a “bad-light day”. My first thought was: that’s not bad light! That’s beautiful light!

In outdoor photography and wildlife photography, in particular, there seems to be a very narrow window of light qualities that we designate as “good”. This is unfortunate.

Light can do more than illuminate the subject we are looking at. It can, and perhaps should be a part of the story we are telling.

So, I thought I’d spend three posts talking a bit about light in outdoor photography. There are three types of light that are frequently designated as “bad”. Harsh light, flat light, and (often) backlight. Let’s start with the first of those: Harsh light.

Very bright, contrasty, overhead light is typical of mid-day conditions. During my recent trip to Botswana, I was reminded of just how brutal tropical, mid-day light can be – and what a challenge it can be to photograph.

No matter how much post-processing work we put into an image, it’s impossible to magically convert “bad” light to good light. I’ve encountered photographers who won’t lift a camera if the light doesn’t meet some preconceived threshold of goodness. And I find that a little sad.

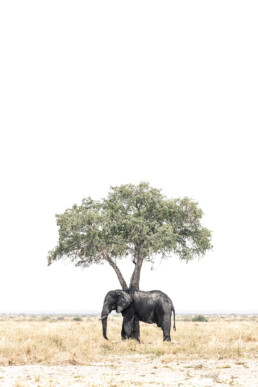

Though we can’t change the light itself, we can change our mindset surrounding it. Harsh light, perhaps more than golden or sweet light, can become an element in the story our images are telling. Take this image:

My group and I found this pair of bull elephants at a water hole in the Savute area of Chobe National Park. It was late morning, and the sun was bright and hot, nearly overhead. Harsh is a good term for it.

If I’d envisioned the scene with sweet morning light, I would have been sadly disappointed, but in these conditions, I knew the sun and the brightness was part of the story. Light can translate to heat in an image, and heat is an element that these animals face many days of the year. Emphasizing, rather than trying to mask the bad light with fancy tricks, seemed like a good approach.

But (and here is the caveat), I didn’t want the final version to be ugly, I wanted it to tell the story. I knew black and white was a likely route to that goal.

In-camera, I went high-key, blowing the sky out to white, and emphasizing the mid-day contrast. Later, back home, I converted to black and white in Lightroom and took that contrast even further, pushing the shadows to black, and most of the highlights to white.

It worked.

Black and white conversions can be a very effective way to cope with harsh mid-day light. You can use the high contrast to your advantage, as black and white photos, often look quite good when the blacks are black and the whites white.

Here is another example from Botswana with a herd of Cape Buffalo:

Low saturation, but not quite black and white can also be effective. Try to bring out too much color in high contrast light and you are likely to end up with something that looks closer to a comic book than a photograph. Don’t make that mistake.

Sepia tones like these two photos are something to consider:

Or low contrast, high key images, like these can also be effective. In these, I did my best to retain the natural, mid-day color of the grasses and trees, but purposely blew the sky out to white.

In the case of this shot with the single elephant beneath the small shade tree, I think this is one of my best images of this trip to Botswana. It’s not beautiful, but it tells a story.

This final photo I made while leading a wilderness trip to the coast of Katmai National Park. The only client on the trip was photographer Mario Davalos. I adore Mario’s work, but at the time, I didn’t really get his way of seeing the world. (I learned from him, gratefully, and this was one of many lessons). We were flying low in a bush plane, down the coast of Katmai when we spotted this bear clamming out on a mudflat. There was plenty of room to land, so we told the pilot to put us down on the beach. We unloaded and walked the short distance up to a good view of the bear. Mario sat down on the sand, braced his camera, and peered through the long lens of his telephoto. “It’s soooo beautiful…” he said.

I didn’t really believe him. The light was harsh and contrasty and did not fall into the category of “beautiful” in my mind. But, curious, I sat down and raised my own camera. And it was beautiful. Not typical, but beautiful. Thanks for that lesson Mario, it’s not one I’ll forget.

In conclusion, it’s time to readjust our mindset of what good light looks like. We talk about the importance of stories in our photos, but then give up on telling them when the light doesn’t meet our preconceived notions of what good light looks like. Your camera technique is more important than normal. In-camera exposure, for example, matters even more than during golden light conditions. Most importantly, you need to consider how the final image will look before you click the shutter.

Think it through, but make the shot.